Description

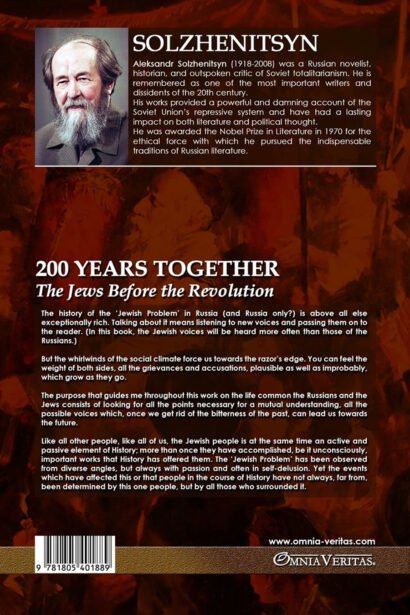

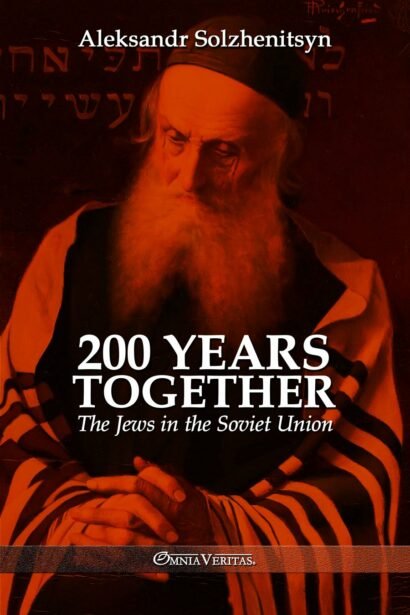

However, it took time for me to realize the importance of that distinct historical boundary drawn by mass emigration of the Jews from the Soviet Union that had begun in the 1970s (exactly 200 years after the Jews appeared in Russia) and which had become unrestricted by 1987. This boundary had been abolished, so that for the first time, the non-voluntary status of the Russian Jews no longer a fact: they ought not to live here anymore; Israel waits for them; all countries of the world are open to them. This clear boundary changed my intention to keep the narrative up to the mid-1990s, because the message of the book was already played out: the uniqueness of Russian-Jewish entwinement disappeared at the moment of the new Exodus.

Now, a totally new period in the history of the by-now-free Russian Jewry and its relations with the new Russia began. This period started with swift and essential changes, but it is still too early to predict its long-term outcomes and judge whether its peculiar Russian-Jewish character will persevere or it will be supplanted with the universal laws of the Jewish Diaspora. To follow the evolution of this new development is beyond the lifespan of this author.